My mother removed my legs and wrapped them in cheesecloth—no lint—before putting them in the top drawer of the bureau beside my crib. “Tell me the story again,” I displayed on the message screen embedded in my chest.

“We had a choice,” she said, smiling down at me. “You were born with only one good leg, the other had no fibula. Since we were both athletes, and that was our plan anyways…and since there was precedent…” She waited for me to say my part.

I flashed, “Blade Runner, the 2012 Olympics.”

“It was only natural that we assumed, since you came from athletes…”

Again it was my turn. This one I felt unsure about, but I never let her know that. I simply displayed my line. “I wouldn’t want to spend my life limping like a geek.”

“Of course not sweetie.” She started to detach my arms where they screwed into the sockets of my shoulders. Talking all the time about how they replaced my legs. Then how, when I was six, I fell on the front lawn in a game of chase I was having with my sister. Pretending to be a Transformer, she drove the riding mower over my right arm.

“Since we had to replace your forearm anyways,” my mother said, tucking one of my arms between her elbow and side as she walked around the crib to remove my other arm. “And you could get two at a discount…”

“It only made sense,” I responded on my screen with the lines she’d taught me.

“But just before they wheeled you in to operate, I noticed the webbed prosthetic on the last page of the catalog—they were new back then—and I yelled down the hallway.”

“Hold your horses.” I gave her a smiley face at the end of that.

“Because I knew….” She took my arms and draped them over the wooden bar in the closet. “Given the genes you came from, it was only natural to think…”

“Triathlon.”

She took the tool from the top of the bureau and opened the plate to lubricate my engine. This we never talked about. She had it installed that time she got really mad at me. I was not quite twelve and I was losing every race. She was angry at my lack of desire. “You have no heart,” she told me after one particularly humiliating loss at a pre-Olympic trial. I couldn’t tell her the two boys I let finish ahead of me (so I wouldn’t have to hear their taunts at my back) had spent all week calling me Tin Man, refusing to let me sit with them, or anyone, at lunch. Or join them in the game room at night. “No freaks allowed.” I thought if I lost, they might like me.

“The rest is history,” she said. She blasted air into my engine then, like always, she closed me back up with a final flourish, one last wrist-twist to tighten the last screw. “Three Olympics, fifteen medals. You could’ve had more.”

“You didn’t want to be greedy,” I displayed.

“That’s right, leave some for the ‘able-bodied’.” She laughed. “Two each in swimming and running, and of course the triathalon.” She lubricated my vision slits—we called them eyes in public—then buffed the peak of my head, the pointed top of the aerodynamic implant fused on when I was fifteen.

She snapped the crib sides up then snapped the nutrition cord into my stomach portal. “Sweet dreams,” she said and turned to the door.

I beeped to get her attention.

She halted, confused at this change in our routine. “Yes?” She stepped closer.

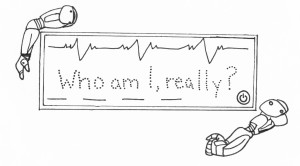

Slowly, one letter at a time, I spelled out, “Who am I, really?”

She folded her arms across her chest and shook her head, as if marveling at me. “Why honey,” she said, unfolding her arms to grip the crib railings. “You’re my little bundle of joy.”

Illustration by Katherine Villeneuve