{From Press Street’s Room 220}

Athanasius Kircher, a seventeenth-century German Jesuit and self-styled “master of a hundred arts,” is credited with inventing the megaphone, a pre-cursor to the computer, and (perhaps) a cat piano. His intense curiosity about the world around him motivated him to pursue studies in fields as disparate as magnetism and magic, optics and acoustics, Egyptology and volcanology. He and his work have been widely researched by scholars, but until recently have never been the subject of a general-interest book.

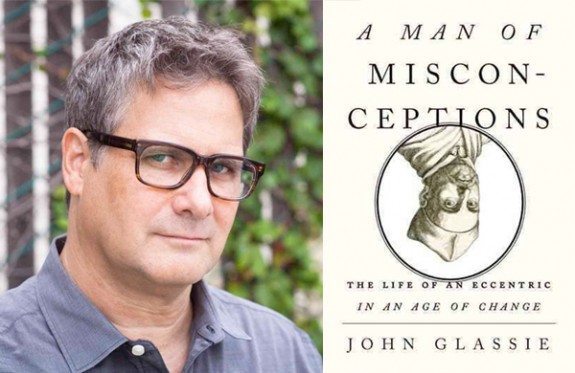

This winter saw the publication of A Man of Misconceptions: The Life of an Eccentric in an Age of Change, an accessible and entertaining biography of Kircher by former New York Times Magazine contributing editor John Glassie. Glassie will present his book at 7 p.m. on Monday, April 22, in the Audubon Room of the Danna Center on the main campus of Loyola University New Orleans (6363 Saint Charles Avenue). The lecture will be preceded by an exhibition of the 1667 print edition of Kircher’s China illustrata in Special Collections on the third floor of Loyola’s Monroe Library from 5:30 until 6:30 p.m.

Room 220: How did you first come to be interested in Kircher, and what made you want to write about him?

John Glassie: I really became fascinated with him after being asked to write an essay to go with a series of images selected from Kircher’s books. This was in 2005, for a visual-culture annual called the Ganzfeld that’s unfortunately no longer being published. Kircher wrote more than thirty books on almost as many topics: magnetism, music, medicine, optics, acoustics, cosmology, Egyptology, geology, and a lot more. Many of them are a thousand pages long and they’re filled with beautiful engravings as illustrations. I took some academic material about him home with me and I was just blown away by it all. There was no general-interest book that told his story, and I just felt like it had to be done.

Rm220: Kircher lived at a time when many familiar ways of thinking were being edged out by new ideas. As you put it in the book, he was born into a world where most people believed the earth was at the center of the universe, but by the time he died, the earth had been displaced by the sun. We’re also living in age of profound scientific and cultural change. Are there lessons that we can learn from Kircher’s life and his response to change?

JG: I think that many of the things we’re absolutely sure of will turn out to be wrong. I think we can count on looking silly to future generations of humans because every era does. Kircher ended up looking foolish in part because he held onto some conventionally held notions of the day—astral influence, for example, or the idea that small living things such as insects, frogs, and snakes are born spontaneously from decaying matter. He also believed in the hollowness of mountains and something called “universal sperm.” At any rate, I think it’s important to maintain both an open mind and some healthy skepticism, and to try not to fall in love with our own ideas.

Kircher’s “China illustrada” contains elaborate illustrations of social and natural phenomena in the Far East, including the flying turtles of Henan (pictured). An original 1667 edition of this book will be on display in the Special Collections room of Loyola’s Monroe Library preceding Glassie’s talk on April 22.

Rm220: If you had been alive in the 1600s and had met Kircher, do you think you would have like him?

JG: I think so. He was lively, really brilliant, and very charismatic. It was his charisma, along with his willingness to fudge the truth a bit, that landed him in Rome, where he rubbed elbows with popes such as Urban VIII and Alexander VII and great artists like Bernini. As I describe in the book, he told great stories from his youth about surviving stampeding horses, a mill-wheel accident, a bad case of gangrene, and the armies of an insane Bishop before winding up there. And he delighted people who came to visit his museum in the Collegio Romano, the Jesuit college there, with the things he had on display: magic lanterns, speaking statues, the tailbones of a mermaid.

Rm220: Some people—Descartes among them—apparently found him a bit off-putting.

JG: Descartes wrote that Kircher was “quite boastful” and “more of a charlatan than scholar,” but he never met him—that was his reaction after thumbing through Kircher’s great big book on magnetism, first published in 1641. The interesting thing is that Descartes wasn’t actually quite as dismissive as those quotes make him seem. He was very intrigued, if also skeptical, about Kircher’s claims that he could drive a clock with a sunflower seed. The idea was that the seed would turn to follow the sun the way the sunflower itself does—that it was drawn by the magnetic attraction of the sun to do so. Descartes didn’t find the idea to be so ridiculous that he didn’t try it himself. (It didn’t work.)

Meow meow meow MEOW meow meeeooowwww meow meow me me me meow meow meow meow MEOW meow meeeooowwww meow meow me me me meow meeeooow meow meow

Rm220: Kircher is often remembered, when he is remembered at all, for his supposed invention of the infamous cat piano.

JG: Right. Actually there’s a cat-piano i-Phone app now—so you can give a concert on one and no animals will have been harmed. Actually, it’s not clear he thought it up, or that he ever made one, but it has always been attributed to him.

Rm220: So, for what should we remember Kircher?

JG: I’ll pick three things off the top of my head out of a couple dozen: coining the term electromagnetism, inadvertently investing Tarot cards with the occult significance we now associate with them, and confounding or stimulating a lot of great minds of his time.

Rm220: You’re a bit of a Renaissance man yourself. Your previous book was a collection of photographs of mangled bicycles chained to poles. Do you fancy yourself a modern-day Athanasius Kircher?

JG: I’m really more like a dilettante than a Renaissance man, certainly as compared with Kircher and other polymaths of his era. Those guys blow everybody out of the water. Kircher knew perhaps a dozen languages, experimented with an algorithmic approach to music composition, pursued his interest in geological matters by climbing down into the smoking crater of Mount Vesuvius!

Rm220: What’s next for you after neglected bikes and quirky Jesuits?

JG: My standard answer is “something easier.” This was a pretty hard project. It might have to do with an 18th-century raft trip or a beatnik Hollywood photographer.

Interview conducted by Dr. John Sebastian, Associate Professor of English and Director of the Medieval Studies Program at Loyola University New Orleans.