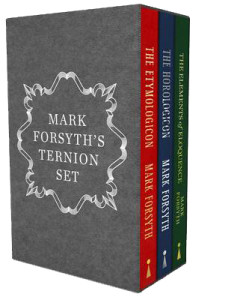

Mark Forsyth’s Ternion Set: The Etymologicon, The Horologicon, and The Elements of Eloquence. Icon Books Ltd, 2014. 768 pages.

Chances are, you’ve felt at a loss for words.

There’s a word for that.

The French call this ailment l’esprit d’escalier. Literally, it’s “an afterthought that comes to one—after the moment in which it would have been useful—while sprinting down the stairs.” In English, it’s merely “staircase wit.”

If you’ve felt this red-faced frustration, or similar exasperations with the English language, author Mark Forsyth might have a solution for you.

To date, he’s written a total of three lexicons: an etymologicon, a horologicon and a manual on the art of turning phrases. Between the three, Forsyth has amassed a collection of knowledge so extensive it’s guaranteed to ensure you’ll never be grasping for a word you don’t know again.

Forsyth’s practice delving into and dissecting words is much more than for impressing people at cocktail parties or toastmaster’s speeches. It’s a continual labor of love on the author’s part. Forsyth regularly updates his blog on his findings, The Inky Fool. Much of its content has inspired Forsyth’s books or what he refers to as his “papery child[ren].” In their respective pages, he sets out to prove that English has an abundance of useful words and forgotten histories within them. They’ve become trapped somehow in idle pools of stagnant backwater and forgotten yellowing dictionaries. Forsyth has sifted through those texts so that you don’t have to.

The Etymologicon: A Circular Stroll through the Hidden Connections of the English Language was the first of these. Published in 2011, it is comparable to an archeological voyage into the origins of each word from the biblical to the boudoir. Words are revealed as fossilized stories. Forsyth traces back the word “magazine,” to its roots in Arabic’s “khazana,” explains “humble pie” and what exactly “umbles” are, and likewise, Leopold Ritter von Sacher-Masoch’s relationship to sadomasochism. Forsyth himself implies he wrote the book after discovering his extensive knowledge of word origins had turned him into the nuisance of family members, strangers (possibly even partygoers and dinner guests alike). His enthusiasm is quite contagious, and any reader will likely feel themselves compelled to share their discoveries and unable to shut up about them.

The Horologicon: A Day’s Jaunt Through the Lost Words of the English Language (2012) on the other hand, is more like uncovering forgotten antiques—perusing a cache in hopes of finding something of reintroducing some of them today. The structure, unlike the other two, creates a specific narrative—following the events of what might be considered a typical day—and using it as the vehicle by which it appropriately inserts and interjects its vocabulary. What better a word than “elflocks” for the tangled mess you discover your hair has become upon awakening? Or, relevant to the upcoming 2016 election, “a snollygoster is a fellow who wants office, regardless of party, platform or principles, and who, whenever he wins, gets there by the sheer force of monumental talknophical assumnacy.” Definitions for wamblecropt, hum durgeons, and hypnopomps await in its pages.

The Elements of Eloquence: How to Turn the Perfect English Phrase (2013) is the most recent of the three. While the other two reference books are amblings through subjects Forsyth may choose to blog about on any given day, The Elements of Eloquence is his tour de force. In it, he dissects entire passages by Shakespeare, while making the case that much of the Bard’s craft was perfected due to the sort of rules considered crucial to a well-rounded education in his day—knowledge and practice in employing certain techniques upon which his witticisms were founded. In these pages, Forsyth makes a strong case for learning to identify the flowers of rhetoric before planting a garden of one’s own. The various examples give proof to this. For one, it’s argued that Hendiadys can be found in Shakespeare’s most famous texts. In another example, we see how Raymond Chandler makes usage of synaesthesia—a technique by which one receives cross-wired sensory details.

It is the author’s sense of humor and genuine curiosity that propels the reader through each text. Unlike the aforementioned dictionary or thesaurus, the structure of these installments isn’t as alphabetical as it is whimsical in nature. There is, of course, a list of contents or a corresponding glossary (if you’re looking for something in particular). Still, it is precisely this element of free association on part of the author’s voice that creates a narrative arc. From beginning to end, readers are assured that not only is there a word for what they’re thinking of, but a quick, entertaining explanation for where that word comes from too.

Forsyth’s interest isn’t turning his readers into ivory-tower sesquipedalians nor does he have any delusions of grandeur. Each book is merely a series of stories seamlessly transitioning from one word to another. While happily taking on the mantle of preserving and imparting these histories, the underlying theme in all three is that language, just like falling objects, seek a kind of center of mass—spoken words eventually reach a perfection of their sound. Forsyth’s books and his blog, demonstrate knowing the history of words enriches living in the world itself. Even as the language we haphazardly employ is constantly changing and evolving, perhaps we might look to the past and these resources for continuing inspiration.

There is, it turns out, an English phrase for l’esprit d’escalier: tintiddle.