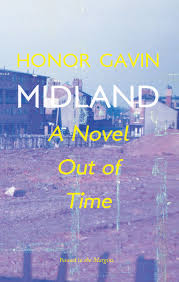

Midland, by Honor Gavin. Penned in the Margins, 2014. $15, 320 pages.

Recently short listed for the Gordon Burn Prize, Midland is ostensibly a novel about the English midlands, and in particular, the post-war urban history of Birmingham. The city, which is so central to the narrative it even has a small speaking part, however, is never given its proper name. The same is true of the novel’s three female protagonists, the bab, ww (working woman), and Rita (who remains entirely nameless until near the end of the novel). These are the three girls that Midland chronicles. As the novel progresses, links between these women are revealed, but this is not a novel woven out of ancestral or chronological threads. Honor Gavin describes Midland as “a novel out of time,” suggesting the difficulties of pinpointing precisely what this novel is about. In her first novel, Gavin has chosen to fray rather than weave, layering the bombs of WWII, the modernist construction boom of the 1960s, and the industrial decline of the 1980s into a single urban cartography of destruction and construction.

The bab is the second heroine we meet. She has found wartime work as the personal secretary to the City Surveyor, Humphrey B. Manzino (a character based on the civil servant, Herbert Manzoni, known for his unapologetically modernist remapping of central Birmingham in years after the war). The bab is charged with an enormous map upon which she marks the “gaps and pants” that the German air raids leave in their wake. Each day she listens to the shell-shocked people who queue at her desk. Meticulously, she traces the destruction of their homes and business. The map, color-coded according to bomb-type and bomb-damage and detailed to the point of illegibility, is a poignant symbol for the way Gavin intermixes the themes of construction and destruction. But as curious as what is drawn on the map, is what is placed on the map:

The three paperweights that keep the map steady are as follows: a pumice stone, a bag of sand, and a single piece of white chalk. … Each object has, the bab feels certain, some sort of talismanic significance, but what exactly that is she isn’t sure. To be honest, she hasn’t got a clue.

The bab’s uncertainty or indifference about the “talismanic” meaning of the these three objects suggests Gavin’s own relationship to those literary things that “hold down” novels–plot, character motivation and genre. The arbitrariness of the objects on the bab’s desk echoes the arbitrariness of the particular details Gavin collects is her narrative. Her writing style, too, has the feeling of being somewhat cobbled. The prose slips from the lyrical and dream-like to the expository and matter of fact. At times, Gavin sucks you into an unsteady landscape of fractured objects and meanings: “Jewellery jigging and jewellery buried. Sand everywhere. Sand in joins and in the machinery and in an earhole. And in the sand: crunched bedsteads and gravestones.” Other times, she lists details and objects coolly as if they were items on a shopping list. Either way, it is the talisman-like miscellany of objects and styles, rather than their consistency, that make up the world of Midland.

Gavin’s novel is full of perfunctory “thingness.” But embedded in this focus on the weight and texture of ordinary things is the sense that Gavin is trying to scratch at the boundary between the physical and immaterial world. Midland does not suffice to describe the material world, or to use the material world as a set of symbols for the immateriality of human experience. Instead, it is as if Midland was carved into the physical world as a pupil might carve her name into a wooden desk. It is at just such a desk (in the real-life and recently demolished Birmingham Central Library) that Rita learns about the building techniques and materials that (thanks to Manzino) had so drastically changed the landscape of her city. It is this cool and brutalist surface that Rita longs to etch herself into as she wanders feverish through the semi-real landscape of the city.

Near the end of the novel, the prose begins to wobble back and forth from third and first-person narration. Rita is thrilled to learn that writing her name can be a form of rebellion:

The first time I had been properly told off was for writing my name on the Head Tis’er’s notice board. […] I hacked out an R, slashed an I, mis-matched the trunk of a T with its branches but decided to let it stand, and cracked out a dagger of an A: I smiled vigorously. I was heroic. […] My signature was my first crime. RITA’s sin was my surrender: my eyes seared when she was reprimanded, but in some obscure internal organ — the spleen, or maybe the gallbladder — I was thrilled. RITA was doing OK.

The act of scraping a word into a desk or scrawling your name on a blackboard when the teacher isn’t looking, reminds us not only that writing requires a material surface upon which to take shape, but also that writing can be both an act of creation and defacement. In this scene, innocence and violence come together as an act of rebellion, which is really the point Midland is making throughout. With the proverbial “I was here” of petty vandalism, we get at the heart of Midland, a story about the difficulties of being ourselves only objects in the world. The “I” that Rita “slashes” into the board is not simply one of among several letters that make up her name. It is also, of course, the pronoun under which we all must struggle to cobble together, out of material and immaterial things, the great fiction of being a first person.

If early novels were preoccupied with the sense that fiction is merely a substitute for “a just history of fact,” as the presumptive editor of Robinson Crusoe has it, Midland is a novel actively seeking the fiction through which we cobble together the world out of arbitrary things. Arching from the modernist optimism of post-war Britain to an era of post-industrial, post-modern decline, it is easy to see Midland as a cultural prehistory of our contemporary state of political ambivalence, gentrification and austerity. However, if Midland represents the history of a particular time and place, it is also about the dislocated time and place where material things like a bag of sand, a piece of chalk and wooden desks, meld with immaterial things: love, pain and desire. Out of time and out of place, Midland is a testament to the history of the Midlands, but also to the encounter between violence and creativity that forges more abstract places for living.

Christien Garcia is a writer and PhD Candidate in English at McMaster University in Hamilton, Canada. He invites you to read some of his writing at whenwebuildagain.org.