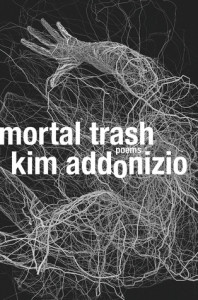

Mortal Trash, by Kim Addonizio. Norton, 2016. $26, 107 pages.

Kim Addonizio’s latest collection emphasizes what she writes about best: sex, relationships, and death. But Mortal Trash refines these concepts and their connection to waste or recovery. Whether meditating on the death of loved ones or the aesthetic limits of poetry, Addonizio exposes the potential disposability of everything and everyone with her usual wry combination of humor and seriousness. In Addonizio’s poetry, relationships are never simple. When people try to connect, they develop an awareness that simultaneously plunges them in the moment yet forces an acknowledgement of broader concerns. In “Plastic,” the speaker discusses the power of romantic and sexual relationships while ruminating about the garbage patch in the Pacific Ocean. Her environmental conceit culminates in the exhortation to “[t]hink of the Earth as a big snow globe” and to believe:

Even if your love is brighter than the sun,

the ick of snow keeps falling.

Everyone feels a little tender

when stabbed with a fork.

The emotional pain of relationships and the physical friction of sex become inseparable from the damage striking Earth. While human beings often feel encapsulated in their own worlds, so much is happening beyond every single sexual act or relationship that it seems overwhelming to think about, let alone do anything about. Many of the poems tackle the link between sex and death, responding to classic poems with a postmodern twist. For example, she re-envisions one of John Donne’s most famous poems, Holy Sonnet 14 (“Batter my heart, three person’d God”), in her poem “Except Thou Ravish Me”:

Batter my heart.

Burn me with a cigarette.

Show me your dick.

I am fuck-sick.

Addonizio’s poem emphasizes the masochistic wishes of the original. She shifts the focus away from God to erotic desire, showing that Donne’s religious intention to be ravished can be interpreted in other ways that propel sensuality toward violence. While many of the poems in that section appear to eschew form, Addonizio has also written a series of sonnets as reinventions of Shakespeare’s cycle. Notably, she takes on the challenge of modernizing his most famous sonnet, number 18. She turns toward brutal confession to the beloved: “I couldn’t compare this to anything”; “April has a hangover winter was terrible”; “I don’t know how I am;” and “Death still has bragging rights / this line has stopped breathing.” Although Shakespeare focuses on the usurpation of death, his sonnet assures that poetry and the subjects it describes can survive it; however, Addonizio shows that everything is ephemeral: weather, beauty, even knowledge of oneself. This break from an ability to express oneself fully is illustrated further in some of the later sonnets. In some of them, Addonizio writes empty brackets or parentheses, such as in sonnet 126. This particular poem’s last two lines are nothing but empty parentheses, an elision of language that reflects fragmented consciousness or an acknowledgment of what is unsayable or perhaps what is left unsaid, considering the brutal power of death to separate lovers. Looking at Addonizio’s metacognitive approach to writing poetry about poetry reads both as a how-not-to treatise and provides humor, which evens out the heavier topics. “Introduction to Poetry” stands out as an imaginary poetry workshop. The speaker claims,

Breasts are more poetic than penises

or vaginas. Or sunsets.

But better a penis and a vagina than a sunset,

especially a sunset over the glittering ocean, over the craggy peaks.

Not only does the poem remain comical, but also it displays the casualness with which Addonizio can write words that appear always already hackneyed in poetry. The poems lapses into parody, naming and combining as many clichés until it folds in on itself. Addonizio even channels Elizabeth Bishop, who is mentioned as the only one allowed to write about rainbows, when the speaker, sick from the frustration of paltry language, finally urges writers to write, an allusion to Bishop’s “One Art.” While this poem presents writing as a staggering task, the truth Addonizio expresses is that at some point, every writer writes garbage: clichés, dead metaphors, and opaque turns of phrase. The trick is to decide whether a specific piece of written can be recuperated and turned into something workable or should just be scrapped. Despite the occasional levity of the collection, the poems in the last few pages contemplate mortality the most intimately. Some of the poems meditate on the deaths of her mother and brother while others point toward an existential awareness of not only one’s life but also the lives of the human race. While other poems like “Plastic” may address impending environmental disaster, the epistemological disasters envisioned in “The Givens” questions why human beings even exist. Every day we take so much for granted; it is a given people will be rude, that toilets will break, or that people will vomit after “too many mango-cucumber-cocktails made / from a recipe by Martha Stewart.” However, we often may not want to try not to consider it a given why “Someone will pull you from the fire, someone else wrap you in flames.” While we may accept the smaller cruelties of daily life, it is harder to accept why we are here to experience seemingly endless pain, loss, and grief. Life seems like a trap, and mortality is both escape and prison of another kind if we expect to continue suffering until, during, or possibly after death. While this collection sounds as if doom prevails, Addonizio strikes a harmonious balance. Death is inevitable, but only for those who have lived. Everything we make, everything we are will be discarded one day, but Mortal Trash is not so much a threnody as it is a praise song of human life in all of its sordid, broken, and at times terrifying beauty.

Justin Holliday’s reviews have previously appeared in The New Orleans Review, Lehigh Valley Vanguard, and The Adroit Journal. His poetry has been featured in Queen Mob’s Teahouse, Glitterwolf, Sanitarium, and elsewhere.