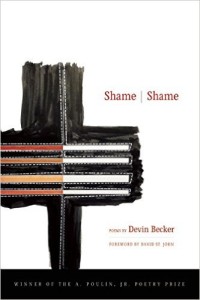

Shame|Shame, by Devin Becker. BOA Editions, 2015. $13, 104 pages.

To say the poems in Devin Becker’s new collection of poetry, Shame|Shame, are about shame misses the point. Rather, many of these poems deal with a particular variety of internal bifurcation shame engenders—a self that is banished from the self. For Becker, internal exile leads to a world in which meaning unravels and identity erodes. What is remarkable about these poems is the way in which, despite their consistent postmodern destabilization act, they achieve a sincere and relatable sense of human yearning for the very identity shame and high irony undermines.

Formally, these poems often capitalize on the internal discord. In “Restaurant,” a prose poem with a third person narrator, a nameless protagonist sits at a bar, ruminating on his life, literary endeavors, and shortcomings. The protagonist slips into internal dialogue and fecklessly argues with himself. “I’m learned I’m learned, he mocks himself. / Fuck. I’m fucked. / Fuck you. / No, no.” These moments of discord rend the self apart and forefront the irony that runs through much of Becker’s collection. The self sees through the self’s naivety, says one thing and then, in the same breath, undermines the sincerity of what has just been said. As a result, the speakers and protagonists of these poems are never quite able to be where they are or mean what they say.

Often, in Shame|Shame the identity of the “poem” as a literary form is equally dubious as their speaker’s assertions. The narrative prose form suggests its own subtle irony by refusing the traditional poetic form. And even those poems that register more conventionally as “poems” often draw attention to their structure, destabilizing their own form. The speaker of “Mirror stage,” for instance, begins with:

It’s the sound, I don’t like, the Sound of Poetry.

The pausing and the drawings out. The da-Da-da-Da-Da rhythms toiling to convince you You…are on the receiving-end of Wisdom.

Or worse: pregnant white spaces.

While the internal dialogue creates its own verbal irony and consequent internal exile, formal irony sends the poet into exile from his own craft. Yet, as the poems’ very presence indicates, the poet continues.

In a way, this almost Hamlet-like, ironic and self-reflexive disposition reads as redemptive, as if at the center of shame exists an admirable intelligence that, by virtue of its internal exile, is able to rise above the self’s pretense and naivety, and end up better, more authentic, more original, more individual as a result. In this sense, Becker’s poems internalize what David Foster Wallace diagnosed in his essay “E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction” as the deployment of irony in American advertising. Discussing an Isuzu ad that references its own status as advertising, Wallace writes:

The ads succeeded as parodies of how oily and satanic car commercials are. They invited viewers to congratulate Isuzu’s ads for being ironic, to congratulate themselves for getting the joke…The ads successfully associate Isuzu-purchase with fearlessness and irreverence and the capacity to see through deception.

Yet, Becker’s poems resist the alienation of irony that Wallace critiqued. Here lies the true triumph of Shame|Shame. For Becker, the disenchanted self reaches past a self-congratulatory tone toward irony’s antitheses—feeling, and vulnerability—thus answering Wallace’s call for a new sincerity in an unforeseen way. Rather than bald sincerity, as Wallace forecasted, these poems use irony to achieve the very kind of sincerity that irony tends to parody.

As Wallace points out, a problem with postmodern irony is that it can lead to nihilism. “Make no mistake,” Wallace says, “irony tyrannizes us. The reason why our pervasive cultural irony is at once so powerful and so unsatisfying is that an ironist is impossible to pin down.” Becker’s poem “Water Fountain” serves as a good analogue for this tyranny. The speaker of “Water Fountain” lists a number of events he can’t remember:

I don’t remember what we fought about near the water fountain

I don’t remember the way the air felt on my skin in the winter when my sled slid out off the bank and skidded across the river

I don’t remember the taste of watermelon in the summer. Watermelon in any season.

The speaker’s insistence on not remembering proclaims his refusal to be pinned down. Sincerity is rendered ironically—through refusing to remember what one is remembering. The content is neither here nor there. Toward the end of “Water Fountain,” the speaker says “I don’t remember anything useful / Like how purely Me I felt when I was young and it was my birthday.” The speaker’s failure to remember hasn’t changed, but the nature of the absence is thrown into high relief. The result of the speaker’s failure to remember—perhaps a product of shame itself—is a lost a sense of self. After shame’s siege, the speaker can’t even remember what it’s like to feel like himself. The sincerity of this loss comes across as very real.

Even those poems that aren’t as ironic in tone or form still reach for a similar theme—that yearning for meaning and identity that irony and shame throw into question. In “Ex Nihilo,” for instance, the speaker juxtaposes feng shui with religion:

Can we make a religion out of interior positioning? We can.

Can we make one out of your hands? As long as they touch noth-

ing, but refuse temptations

to make something from it.”

(God tried that before, made us in the image of his wanting.”

To refuse the temptation to make something out of one’s own refusal of temptation is to relinquish the desire for any particular meaning. This lacuna of import, of substance—not unlike the interlineal white space of the line itself—is carved into that most sacred arbiter of meaning, religion. But religion’s internal commandment, its very mechanism, undermines its ability to make meaning or sense out of itself, perhaps because it would be shameful to do so, or at least selfish. By doing nothing, religion forecloses the possibility of a self to be selfish in the first place.

The absence of meaning becomes the presence of yearning for meaning.

The inability to find meaning in the authority of religion and the concomitant lack of self finds its atheist analogue in the postmodern condition. The reader is tyrannized by the same ironic spirit Wallace astutely critiqued. Yet, “Ex Nihilo” reaches beyond this inability to create meaning toward something very meaningful. God made us in “the image of his [God’s] wanting,” the speaker says, and it is this very wanting that becomes the substance of the poem. As religion undermines itself it creates the spiritual sincerity of yearning in its own absence. So, too, with the postmodern world. The absence of meaning becomes the presence of yearning for meaning. In Becker’s hands, identity and sincerity may be things of a bygone era, but that doesn’t mean a sincere yearning for both is obsolete.

“Kristin,” another short, free verse poem, gets at this experience best. The speaker, lying in bed with his wife, asks her about “Indianapolis,” the poem directly preceding “Kristin.” He writes, “I let Kristin read one. Not one she’s mentioned in, or the sex one, the one where I get drunk, with Michael, at a strip mall.” The self-referential content in “Kristin” once again sets in motion that tyrannical irony Wallace critiqued. This is compounded by Kristin’s response: “She doesn’t like it. / She says Geese have no morals sounds like an ending and she doesn’t like that sound, the wrap up sound.” As Kristin, the character in the poem, critiques the excess of meaning in “Indianapolis,” the poem goes beyond questioning meaning to questioning the means of questioning meaning. In this thicket, yet again, is a glimmer of sincerity, and it hangs on the void that meaning once occupied.

In response to Kristin, the speaker says, “I can’t resist myself, I’m sorry.” It’s the speaker’s confession of his naïve desire to create something conclusive and meaningful that is rendered as shameful. Brilliantly, Becker mines that vulnerability, that shame of desiring meaning, with the very irony that disavows meaning in the first place. In a valueless world, shame is the result of wanting to believe in something in the face of relentless internal questioning and irony, but shame also becomes the productive force of a sincerity that is both invaluable and full of meaning.

In the fallout of a postmodern world, perhaps, we must come to terms with what is tantamount to internal exile. As meaning becomes more and more elusive, so to does identity. As a result shame permeates our want to believe in a self and values that have already been shown to be obsolete. But that doesn’t mean we are barred from yearning for that self, a self that is, in Becker’s words, “purely Me.” There is sincerity in this yearning. And in the face of so much irony and postmodernity, this kind of sincerity offers vital company.

Eric Severn received his MFA from the University of Idaho and has worked as fiction editor of the literary journal Fugue. His book reviews have appeared in Pleiades and Prairie Schooner.