Slow Startle, by Rohan Chhetri. The (Great) Indian Poetry Collective, 2016. $17, 72 pages.

Imagine a poet whose literary ancestry can be found not in a poet or other poets but in a poem. Midway through reading the young Nepali-Indian poet, Rohan Chhetri’s debut collection and winner of the inaugural Emerging Poets Prize from the The (Great) Indian Poetry Collective, Slow Startle, I was reminded of the twenty-third sonnet in Rainer Maria Rilke’s collection The Sonnets of Orpheus, which begins like this:

Call to me to the one among your moments

that stands against you, ineluctably:

intimate as a dog’s imploring glance

Like Rilke, Chhetri is aware of the relational aspect of poetry, where the personal is not self-referential but extends and expands into a relationship with a wider world of meanings. This echo occurs despite Chhetri’s choice to use a poetic style different from Rilke’s, the narrative form. Though Chhetri uses narrative to tell stories, his poetry doesn’t simply illuminate his private life, abstracted from the world of encounters and experiences, a trend that plagues a lot of poetry today.

In the poem “Not the Exception,” Chhetri draws a crisscross of relations, between life, ailment, death, soul body and machinery, and produces a startling aphorism in the last two lines:

The survival of the everyday is a constant

accident from which we will recover in death.

It is not just the facticity of death that lurks around the corner. Daily life jostles, Chhetri writes, with “the precision of machinery outside us.” Surviving the onslaught of machinery that threatens at every corner is a miraculous accident. This relentless encounter with a risk-driven world of technology feeds paranoia. The accident-prone body is astonished to escape and survive the precision of the accident-prone machine. Considering death a relief from this gnawing paranoia, the poet offers a bleak view on our technology-infested era. Chhetri is not interested in raising ontological questions but rather in producing affect that takes readers to the heart of the human condition.

Chhetri is a mood-poet. In the poem “Ghosting,” Chhetri describes a breakup, where the morning of his leaving the house of the lover coincided with a slum burning, as he saw a “funeral of white cranes flew right through / the smoke.” Here a visual description is mediated by mood. The burning slum and the flying cranes reflect the scorching despair of his amorous life. Chhetri’s poems are moody and often originate from memory. There is an uneasy poise with which he expels the excess of remembrance. In the opening line of the poem “Recapitulation,” Chhetri tells us what his sensibility discovers in his craft: “The severity of poetry lies in the retrospect.” What the poem, and the foray into retrospection, reveal are memories harping upon intense events that leave as suddenly as they occur. Like life and death, memories are also intensities produced by chance. Memory too is born of accidents.

In “Mood Elegy,” Chhetri does not simply recapitulate the past but its chronic affectation upon him. The poem ends with a recurrent figure and motif that are part of this collection. First, Chhetri’s preoccupation with the memory of the family patriarch: his grandfather. Second, the animal that occasionally enters and leaves his poems. In three lines of the last stanza, Chhetri overwhelms with a blistering array of metaphors:

The long memory of a bloodline recovering, and the tiger

materializing in the lavatory with the scuff marks

on its flanks and its fur, a disappointing dull orange.

Chhetri could see in his grandfather’s last moments, the disintegration of a body once fortified by animal will, and a slow, painful erasure of lineage that left nothing but blood as a mark of resemblance. Blood is a metaphor that has always served as a racially distinguishing feature, marking the animal borders of human life.

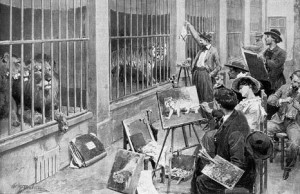

Animal artists at the Jardin des Plantes, Paris. From the magazine “L’Illustration,” 7 August 1902. Photographer Unknown.

In “Elegy Written On A Clock Face With No Hands,” Chhetri spells out his Pessoa-esque belief when he writes, “[He] think[s] of the animal inside us, our double.” Fernando Pessoa writes in The Book of Disquiet through one of his heteronyms, Bernardo Soares: “There is no safe standard to tell man from animals.” It is not merely a matter of the occasional relapsing of the human into the animal, or of the borderless zone lying between them. You simply cannot tell the human and the animal apart. He explores the idea further: “That invisible will guiding the dog across the street / that night.”

Rodin had sent Rilke to Jardins de Plantes, the famous zoo in Paris, to receive poetic inspiration. Enriched by the experience, Rilke wrote his famous poem “The Panther,” where using a neo-classical mode of representation, he described the mighty will of the panther, paralyzed behind bars. What makes the poet feel and name the Rilkean “will”of the animal, which is invisible even to the animal? As a vehicle hits the dog while it crossed the street, Chhetri writes:

it heard its own cry,

and heard the other voice inside it too – the brief

howl that sounded so strange, so unlike its own.

What are we to make of the poet’s claim regarding total familiarity with the dog, its dog-ness such that he heard the dog’s “other voice”? Chhetri suggests familiarity rather than knowledge, for he admits to the presence of strangeness. The claim is still within the contentious realm of the animal being the double of the human. The idea of the “inside,” where the animal lives in the human, marks the strange, invisible, empty center. It is similar to what Rilke discovers in his famous passage on “in-seeing”, where a divinely oriented insight reveals the dog’s empty core. Rilke discovers where the animal in the human and the animal in the animal reside. Does this imply a transference of the human into the animal? No, for the human has already been passed into a double realm where s/he shares the same empty secret.

When Chhetri speaks about his grandfather as a tiger, he means both the man capable of violence his grandmother and the town were scared of as much as the brave man who suffered a jail sentence. We learn the poet’s town is “rife with revolution / dreams of a new state.” Chhetri keeps his political voice muffled, with occasional stark images of violence and resistance. Only in “Violence Enters A Poem Like A Restless Wind Inside A Burning House,” and “A Brief History Of Justice,” do politics of the outside world find their way into Chhetri’s poems. We learn of the Bengali Inspector who had kept his grandfather “hung naked upside/ down for three days, with mud shoved in his mouth.” This is a reference to the movement for Gorkhaland, where people living in the hills of Darjeeling demanded autonomy, still denied by the state of West Bengal.

Though a narrative poet, Chhetri is also gifted with lyric intensity, which adds to his crisp style. Narrative poets are at an advantage if apart from the spell of their storytelling, they infuse fine lyric techniques into the poem. The elegiac tone of this collection also grants Chhetri’s poetry a measure of depth. Poems weaving intense personal narratives need a measured tone to escape the aesthetically blunted influence of sentimentality. Chhetri’s poems have that critical poise.

The “dog’s imploring glance,” from Rilke’s twenty-third sonnet, intimate yet turned away, is a fleeting motif in Chhetri’s poems. As he narrates in “Father’s Day,” when Chhetri was the age of twelve his father hit him for the only time and the poet was taken unawares. His father:

stared at him

from the ground

like a dog that flees when kicked,

and from a safe distance turns

and looks at you.

The discovery of the double in childhood returns with its dog-eyed memory. Like Orpheus in Rilke’s sonnet, Chhetri too leaves many homes – his own, his lover’s, and other homes he would occupy for a brief while. And the “foothold” that Rilke says we long for, Chhetri finds in poetry. The deepest intimacy with anything Rilkean requires turning away from the fixity of meanings or “when you think you’ve captured it at last.” In Chhetri’s poem, “Absolve, Absolve,” this movement is reflected by a deferral of representation. Chhetri explains:

We write to be remembered

For what we failed to name

Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee is a poet, writer, translator and political science scholar. His poems have appeared in The London Magazine, New Welsh Review, Rattle, Elohi Gadugi Journal, Mudlark, etc. He has contributed to Los Angeles Review of Books, Guernica, The Rumpus, Outlook, The Hindu, The Wire, etc. His first collection of poetry, Ghalib’s Tomb and Other Poems (2013), was published by The London Magazine. He is currently Adjunct Professor in the School of Culture and Creative Expressions at Ambedkar University, New Delhi.