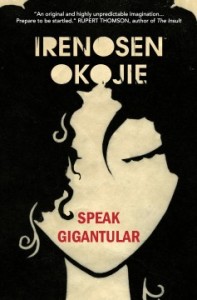

Speak Gigantular, by Irenosen Okojie. Jacaranda Books, 2016. $11, 201 pages.

It is rare to come across a new book where the story or stories told are familiar, but cast in an genuinely uneasy light—one that unsettles while managing to be completely plausible, too close to the emotional truth to be dismissed as total fiction. Those in Irenosen Okojie’s Speak Gigantular should, if there is any literary justice, place her in a circle with writers like Shirley Jackson, Margaret Atwood, and Angela Carter, for her tales here weave together the grand aspects of myths and fairy tales with the dark but all-too-real depths of human nature. The result shocks, for Okojie doesn’t even bother with lulling the reader into a sense of false security, or feeding them a run-of-the-mill story that ends badly. Right from the start, in “Gunk,” she declares herself to the reader with a mother’s words of warning and wisdom to her son, less a loving talk than a war-like acceptance of the world’s evils and the necessity to meet them head-on, as if spoken by a goddess:

Don’t make me transform. Don’t make me reconfigure.

I carried you.

I bled for you.

I suffered for you.

Stay close to me, listen. Every word I say to you is true.

Fuck governments.

Fuck systems.

Fuck everything that tells you if you’re good you’ll be valued.

Someone always has to pay.

Make people pay.

We’ve paid enough.

It’s a cry that echoes Greek tragedies and epic poems in its strength. What follows in each story takes the breath away, for Okojie’s momentum never loses pace. “Someone always has to pay” repeats itself as a terrible theme; what started with Shirley Jackson’s doomed bride-to-be in “The Demon Lover” is continued here, felt like cold fingers on skin in “Animal Parts,” “Outtakes,” and “Fractures”: women who find a little happiness, love, and excitement, only to have it unravel, finding the darker, not silver, lining of their clouds often when it is too late. Love in all its forms is a terrible weight, Okojie seems to say, but in a way that manages never to be completely morbid, instead sharply twisted by the humor and the absurdities of the unreal, fantastic, or simply phantasmagoric, as in ‘Walk With Sleep’ where the two ghosts (three, if you count the ‘living’ image of a Betty Boop cartoon on a t-shirt) of London Underground suicides haunt the lines, sometimes playing with the passengers, at others just listening to their heartbeats; or in “Outtakes,” where Desi imagines her boyfriend to be covered in “pulsing, bloodied hearts … I wanted to ask him, looking at the uncooked meat covering his body, ‘Are you going to eat that?'”

Elena Ferrante has said that she has been influenced by Mediterranean mythology in her stories, and indeed references are widespread within her works. Even if Okojie does not have the same deliberate influence, she has an innate sense of female strength and weakness, and although happy endings are few and far between here, she presents women as in charge of their destinies, regardless of whether that destiny leads them to a tragic end. The point is that they alone hold the power of their emotions and actions—of their stories—while at the same time retaining a self-awareness not always bestowed on female characters. Even after death they retain a strange hold, as shown in “Please Feed Motion,” a story whose protagonist, Nesrine, dies mid-story, leaving “the thing in Nesrine’s throat” as a Siren/Siren’s call, causing the London statues of Eros (Piccadilly Circus), Charlie Chaplin (Leicester Square), Nahla The Bronze Woman (Stockwell), and the Vomiting Fountain Sculpture (South Bank) to come rescue “the thing” and release it into the world. Rather than have the statues come to life, the statues are already alive, a touch which is delightful reflection on Okojie’s ability to see the wondrous in the everyday without coming across as immature: Eros and Nesrine as a neo-Galatea and Pygmalion, and even shades of the Golem: the other statues eating the words of Nesrine’s postcards.

With love, comes otherness: whether it is skin color, death, loneliness, or emerging from the other side of the looking glass, like Henri and his tail in “Animal Parts,” or the garden-homunculus in “Following” who is “plucked … from the garden like a root vegetable,” we are reminded that there are worlds within worlds, fictions are often realities, and vice versa, that given time to unpick, would seem as strange as those we read. But the strangeness—meant only in the positive sense—of the stories in Speak Gigantular are also rich in imagination and the skillful handling of what is and what could be, those delicate threads of life whose potential we often overlook.

Tomoé Hill is an editor at minor literature[s]. Her non-fiction, essays, and reviews can also be read at Berfrois, Numéro Cinq, and 3:AM magazine. She lives in London and tweets @CuriosoTheGreat.