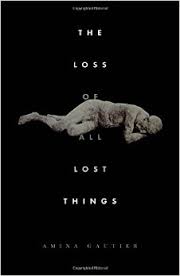

The Loss of All Lost Things, by Amina Gautier. Elixir Press, 2016. $19, 128 pages.

An older white woman who recently lost her ailing husband to suicide stumbles into an affair with a young black male prostitute; a recent divorcee and failed poet finds himself at a writers’ retreat in Wyoming lusting after a painter whose passion for her craft eludes him; a librarian struggling with her daughter’s transition into adolescence seeks the attentions of a blues singing janitor. Amina Gautier’s new story collection, The Loss of All Lost Things, forms a powerful rumination on loss to reveal the complexity of its emotional spectrum. In fifteen short stories, Gautier’s characters journey introspectively through worlds of grief, providing an unfiltered experience of loss and all its aching vulnerability.

A recipient of the Elixir Press Award in Fiction, The Loss of All Lost Things is Gautier’s third award-winning collection. At Risk and Now We Will Be Happy, won the Flannery O’Connor Prize for Short Fiction and the Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Fiction respectively. The Loss of All Lost Things, however, stands out as perhaps Gautier’s most ambitious work as the collection skillfully weaves together multiracial and multigenerational voices to present a collective narrative that is palpable in its emotional resonance. Gautier captures a different aspects of the clumsy reacquaintance with life in the wake of physical and emotional loss. Characters fall into extreme behaviors that are often unsettlingly recognizable. The precision and beauty of Gautier’s prose aptly captures the sensory and wide emotional range of human experience when facing the upheaval that loss creates.

While not a linked collection, themes of interiority and brokenness remain salient threads of the overarching narrative. Many of the stories in the collection also focus on ill-embattled academics in the world of academia. There are two stories in the collection, “Lost and Found” and “The Loss of All Lost Things,” that are distinctly linked in terms of character. I highlight these two stories because of the innovative literary techniques Gautier employs to relay the comprehensive story of a family severed by loss.

The emotional tenor of the collection is set with the opening story, “Lost and Found,” told from the point of view of an abducted child. The story begins with the young boy being absconded from outside his family home by an unknowable stranger he can only refer to as Thisman. Through syntactic repetition and matter-of-fact, unflinching prose, Gautier crafts a perpetual state of stasis for the endangered boy:

“He is lost, but not in the way he has been taught to be. Not in a supermarket; not in a shopping mall. There are no police officers or security guards to whom he can give his name and address. There is no one to page his parents over the loudspeaker to come and get him. None of the clocks where they go give the correct time and there are no calendars to mark the days. He never knows where he is.”

The boy can only mark the passage of time from what he is able to glean from television holiday specials and The Twilight Zone reruns. Words that typically signal transition such as “once” and “today” fail to appoint the boy toward a moment of major change; instead, they precede events that further cement the child’s horrific fate.

Gautier’s deft narrative instincts often lead the reader to be placed in a scene fraught with emotional tension and conflict at the story’s onset. Telling the same story of the missing boy from the perspective of his parents, the collection’s namesake story, “The Loss of All Lost Things,” begins with a frantic neighborhood search for the child. Gautier establishes the joint narrative of the child’s parent’s through the authoritative use of the word “They.” A generative list of the parents’ actions taken to locate the child written in a rhythmic subject-verb patterning create an energy during the opening paragraphs. This sense of urgency is dampened by the reader’s knowledge of the futility of their search. The joint narrative dissolves as search efforts disband and the relationship between the parents begins to deteriorate.

Gautier’s stories invite inquiry as to where loss might lead us. Her stories are tantalizing because they exploit fears integral to the human experience and amplify them through the dramatic situations in which her character’s find themselves. Many of the stories in Gautier’s collection, however, revolve around the lives of individuals in academia. This, coupled with the many clichés she subverts (the lustful librarian, the philandering professor, etc.) enable the collection to operate on two levels: as a meditation on loss and as a satirical commentary on the world of academia. The collection pokes fun at the academic community as it demonstrates their floundering with commonplace, albeit devastating, issues. The stories in the collection that some might view as less successful are those that seem more interested in exploiting cliché rather than exploring it. This can be seen in the story “Intersections,” in which a white professor pursues an affair with a black graduate student. He is fascinated by the intricate design of her braids. Together they drink cheap wine out of plastic cups in her apartment that smells of patchouli oil. Having the graduate student break the fourth wall, so to speak, by announcing that they are living a cliché is not enough to disrupt the story’s all too familiar trajectory. The student breaks off the affair and the professor returns home to his wife.

Overall, the collection provides an enhanced understanding of loss in its demonstration of the ways in which humans seek to make sense of the world following it. This collection confronts the heaviness of grief without hesitation or fear. Gautier does not promise us happy endings or resolve. Rather, moving through this catalogue of promised losses with these resilient characters allows readers to glimpse the reward of landing on the other side of grief.

Chioma Urama’s book reviews have previously been published in Pleiades and her fiction is forthcoming at The Normal School. She is a writer from Virginia living and working in Miami.